When it comes to weird fiction and fantasy, fungi have it covered. They sprout from underneath, spread over the top, and their visionary powers are never far from any surface. This anthology devoted to them features many fatal encounters with fungi, some touching and thought provoking, some predictable mycopocalypses, and some nearly incomprehensibly eccentric shroom trips. In the hardcover version, which includes 3 more stories than the paperback or e-book, many of the selections are followed by a wood-cut-style illustration done by Bernie Gonzales. These images reinforce stark black and white contrasts between good and evil, inner and outer space, the real and the hallucinated, the poisonous and the delicious, and life and death. As the editors put it in their brief and lucid introduction, terror and delight struck them as “an appropriate combination for assembling an anthology of fungal stories.”

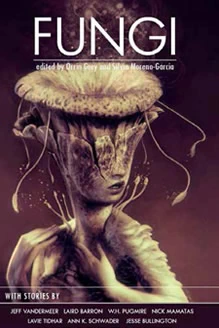

Innsmouth Press specializes in fiction in the H.P. Lovecraft tradition and some of the stories make this lineage quite clear with allusions to Lovecraft’s mythology. As a mycophile, I found the mycophobia of many of these stories excessive but I have yet to tire of Oliver Wetter’s lovely cover illustration. The strongest selections for me were the metaphysical, speculative, and contemplative stories that explore fungicidal tendencies but let us rest in peace. The opening story, for example, John Langan’s “Hyphae,” describes the dementia and death of the narrator’s father as a transformation into mycorrhizal fertilizer. To the narrator, and the reader, the decay is at first banal, then terrifying, but finally serene, described as “the sound of something come home.” Jane Hertenstein’s Wild Mushrooms, perhaps the least weird of the stories, is my favorite because it locates both love and fear of mushrooms in our own histories and hearts. The narrator, a daughter of Czech immigrants, grows up ashamed of her parents’ accent and customs and the dirt encrusted on her hands due to her role as the mush- room cleaner after her parents’ happy foraging. So entwined are the family and fungi that oyster mushrooms colonize the damp basement of their rural home. In his old age, her father disappears on a mushroom hunt.

Months later, he is found rotting in the woods with a morel sprouting at his foot. The moldy family home is sold as a teardown and her mother returns to her homeland where she forages to her hearts content. The nar- rator lives in Chicago, eating mushrooms, when she does at all, bought in Styrofoam. Grief doesn’t fruit in her until she spies, in an expressway embankment, a shaggy mane. Stuck in traffic with plenty of time to harvest it, she leaves it by the road, still behaving like the embarrassed child of immigrants. “I couldn’t think of why I wanted it and the more I pondered, the more I lost my nerve. Maybe it was the tears, blinding me.” In the next sentences, the final lines, the narrator confesses to a subsequent haunting by mushrooms, “in my blood, run- ning through my veins, feeding off the detritus inside me.” Loss and rot joins her finally and permanently to her family.

Art itself also creates a heady, well-balanced blend of oppositions. In the biographical note to “The Shaft through the Middle of It All,” Nick Mamatas explains that he “writes about fungi because of his avid interest in altered states of consciousness. He writes at all for the same exact reason.” This story describes a Lower East Side garden kept verdant by a Puerto Rican woman’s mastery over molds. She also uses that mastery to sicken the inhabitants of a gentrifying high rise that destroys her garden. The difference between flourishing and floundering, she explains to her son, is knowing the right words, the words to say when “the fire burns, and the mold enters the breath. Words I’ll teach you.” The role of art becomes even more explicit in “The Pearl in the Oyster and the Oyster under Glass,” by Lisa M. Bradley. The protagonist, tellingly named “Art” is a bear-like wild creature in human form who leads myco-remediation efforts in various disaster areas. The story closes on the shores of Lake Michigan where oyster mushrooms create a sort of infinity for the planet and its creatures. Frugal and resourceful, the Midwestern clean-up crews harvest the mushrooms after they had been “forced to feed on the poison of human error.” They feast on these deep fried oysters at supper club dinners. When Art joins them at the banquet table, he sees in the mushrooms gleaming flesh the “colour of infinity.” After his first bite, “he swallowed and gave thanks. He was not at peace, but he would eat his piece, and the next, and the next.” In Paul Tremblay’s “Our Stories Will Live Forever,” a writer, hoping for immortality through his writing, begins a plane ride roiled by his fear of flying and his tender artistic ego. His hopes and fears come true, it seems, as he eats a mushroom offered to him by a neighboring passenger. As the plane goes down, his manuscript along with it, his ego and anxiety dissolve into a cosmic optimism of mycelium and hyphae, “fruiting bodies” that communicate in “the tongues of geological age.”

The collection concludes with a list of other mushroom-themed fiction, movies, and television shows. I don’t know how much of the audience for this type of fiction overlaps neatly with mycological society membership, but I am struck by the way so many of these stories explore the kinds of non-fictional experiences that Eugenia Bone describes in the last chapter of her Mycophilia: Revelations from the Weird World of Mushrooms (2011). “Maybe it is no accident that I became obsessed with mushrooms,” she writes. “I think we all search for a way to connect with something bigger than ourselves, and mycology opens that window for me. I may have started out interested in mushrooms because I liked to eat them, but I ended up with a more profound understanding not only of the natural world but of myself as a symbiotic organism living within it.” For that matter, the stories may expand and illustrate what we experience on forays or when we look in a mirror. In Fungi, mushrooms and fungus animate our imaginations, make us human even as they connect us to other life forms, link our past and future, root us to this world and let us see beyond it.

Review by Barbara Ching.

This review was published in the July-August 2014 issue of The Mycophile.

NAMA Store >