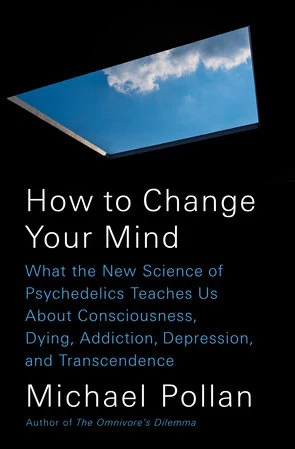

I’ve been reading Michael Pollan since he published his first book, Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education, in 1991. He writes textbook-model exposition and non-fiction narrative, and his signature technique of juxtaposing the scientific knowledge he is conveying with his everyday life testing of this knowledge served him well in his first book and most of his others, including The Omnivore‘s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals (2006) and Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation (2013). In these books, I especially enjoyed Pollan‘s personalized takes on the topics at hand. His latest book, How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (2018.) is no different in structure from Pollan‘s earlier natural histories. Alternating between what he calls telling the story of psychedelic research, past and present and travelogues, Pollan recounts his “trips” on various psychedelics. This time, though, I found the expository parts of the book more interesting than Pollan’s account of his psychedelic experiences—even though his trips range from hunting for Psilocybe azurescens with Paul Stamets and then eating his find several months later, to holotropic breathing, to inhaling smoked toad venom (aka 5-MeO-DMT).

How to Change Your Mind tells a fascinating story about the current state of research into therapeutic applications for psychedelics. While Pollan recounts the stories of familiar, counter-cultural figures in the science of psychedelics such as Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary, he introduces many less flashy but equally fascinating figures in the second wave of research, such as Bob Jesse, educated as a computer scientist/electrical engineer, who now works to move the use of psychedelics into American culture not only as a way to treat psychological distress but also to facilitate the betterment of well people. Likewise, we learn of Al Hubbard, the Johnny Appleseed of LSD who introduced the practice of Shamanism to treat alcoholism in the 1950s—often relying on his own financial resources to provide the treatment. Pollan segues into the institutional difficulties that face this type of research by underscoring the differences between the individual, guided therapies that Hubbard and others employ, versus the control groups (including those given placebos) that characterize conventional pharmacological research. Similarly, he returns frequently to the importance of set and setting in the use of psychedelics, elements that inevitably introduce variables.

While an individual‘s state of mind and environment will affect the psychedelic experience he or she undergoes, Pollan insufficiently recognizes how these factors shape his own experiences. He brings fairly limited concerns to them—an interest in navigating his approaching old age and vague hopes of transcending the ego. He has access to an expense account, contacts, guides, and substances that most readers won’t have. These differences seemed less striking in his books about cooking and eating; moreover, these pursuits don’t pose immediate legal issues. Even without these obstacles, if you had only his account to go on, you might not be especially interested in his travelogue. Pollan experiments with a tiresome doggedness and measures his “results” against a checklist. After his experiment with the toad, he scores 61 points on the Revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire, “one point over the threshold for a complete’ mystical experience”. No matter how much he talks about transcending the ego, he wants to measure up to the psychonauts who preceded him, even as he undermines the very notion of transcendence with this impulse.

Pollan addresses the difficulties he found in writing about his experiences in a New York Times essay published on December 24, 2018. In “How Does a Writer Put a Drug Trip into Words,” he claims that he found two models for this task: Aldous Huxley‘s The Doors of Perception (1954) and the less well-known French writer Henri Michaux‘s Miserable Miracle (1991). Huxley, he argues, is too literary and polished to be authentic and Michaux‘s authenticity makes his account too incomprehensible. Pollan explains that he settled on an approach that speaks to the reader from the visionary perspective of the trip and. in a more pragmatic, pedagogical voice, reminds his audience that one of the features of psychedelia is the ineffable, the superseding of what language can express. He reminded many times.

I suspect the dullness of Pollan‘s trip stories springs from his by now well-worn non-fiction structure and his unimaginative sense of set and setting. While it‘s not surprising that most of the researchers (and literary models) that Pollan reports on are white men, in his sections about the psychedelic experience, surely he could have focused more on experiences of a more diversified group of experimenters in addition to, or instead of, himself. Similarly, Pollan makes no effort to grapple with the question of how his experiences can apply to others. In contrast, in Mycophilia (2011), Eugenia Bone describes her experience with mushrooms more widely. Near the end of her first trip, she decides to take a bath and shares one revelation “with my lady readers of a certain age”: “While in the bathtub, I stopped feeling guilty about growing older and regretful about losing my looks, and then I realized my body was a vessel, like a ship that was taking me through life, and it functions well, and that made it beautiful, and I felt grateful. It was a tremendous relief that I still feel today. She found the words to share this experience by transcending her ego, by recognizing that her set and setting can be connected to the concerns of many other people.

I don‘t regret reading How to Change Your Mind. It’s especially interesting to encounter people connected to NAMA in these pages: Michael Beug, who spoke about his experiences with psilocybin mushrooms at the NAMA 2017 foray, and frequent speaker and supporter Paul Stamets. Most importantly, the book passes the test announced in its title by convincing me that psychedelics do teach us much about the topics listed in the subtitle, that they can help us in our existential struggles and amplify some life‘s joys.

Review by Barbara Ching, 2019

NAMA Store >